Presentation

|

SpeakerYe Ni(The Irrawady) |

Abstract

The global outbreak of Covid-19 has placed an unprecedented situation for the media in very testing times. Most of the news agencies have been working remotely since COVID-19 wave emerged from the end of March in 2020. Journalists and media workers have faced travel restrictions due to the government’s strict new stay-athome orders.

The situation in Myanmar is further challenged by the launch of new Counter-Terrorism Law in Myanmar and the use of fake-news to stop publication of any news on Covid-19.

For the newsroom, the challenges in times of Covid-19 are varied from the personal safety of the team members who are traveling out in the field, at the risk of getting infection, to the dependence more heavily on digital collaboration tools like Zoom. Dramatic changes include online editorial conferences, remote editing, and virtual brainstorming.

Working from home may has made the journalists more efficient comparatively but the quality and creativity of the coverages have suffered to a lesser degree.

The COVID-19 outbreak in Myanmar is currently growing steadily. Daily cases have reached around 1,200 and dozens of deaths in recent days and they have increased from less than 10 per day in early August. During the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, from late March to early August, Myanmar recorded just 360 cases and 6 deaths. On December 7, however, Myanmar reported 100,431 COVID-19 cases, including 2,132 deaths and 79,240 recoveries, according to the Ministry of Health and Sports.

However, the second wave of Covid-19 has overwhelmed Myanmar’s poor and understaffed health infrastructure. Nevertheless, the spread of the virus since day one has led to a partial lockdown of Yangon. The former capital of Myanmar has a population of over 5 million. 67% of Yangon Region’s population live in urban areas, and the remaining 33% in rural areas. Effective as of the 21 September 2020, the government announced stay-at-home orders for all of the Yangon Region.

The government has announced stay-at-home restrictions and curfews, bans on public gatherings, and closures of public events, entertainment venues, and religious places. In the Yangon region, residents must abide by the following orders:

1) Stay at home unless going to/from work.

2) Employees of private organizations and businesses must telework (those working in banking and finance, gas stations, food and refrigeration services, production and manufacturing of pharmaceutical products, medical equipment production, and the distribution of drinking water and personal hygiene items are exempt).

3) Only one person per household is allowed to do grocery shopping, and only two people per household are permitted medical treatment.

4) A mask must be worn at all times when out of the home.

5) Only vehicles transporting people for one of the permitted activities are allowed to pass through other townships.

6) In addition to passenger(s), only one driver is allowed in a vehicle for the permitted activities.

7) Advance approval from the respective ward administration is needed for anything that falls outside of these permitted activities.

Failure to comply with this order will warrant action under the Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases Law1. However, when the government designated essential industries exempted from stay-at-home orders during the lockdown, the Myanmar media was not on the essential industry list. Although several professions are excluded from restrictions, such as doctors, emergency workers, and police officers, the restrictions still apply to journalists. Most of the newsrooms in Myanmar have been working remotely since COVID-19 emerged. And most journalists in Yangon have been reporting from home as suggested by the government. Yet, for photojournalists and video journalists to do their jobs, it’s necessary to go into the field and they have to go out from time to time.

Whenever journalists are on the streets, they are concerned that they will be arrested and charged under the Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases Law. This restriction also stops the work of drivers of newspaper delivery trucks. As such, lockdown restrictions have impacted on the media industry, particularly the production of newspapers since all private national newspapers are based in Yangon. Four national newspapers, The Standard Time, 7 Day Daily, the Myanmar Times, and the Voice Daily announced their decision to suspend circulation of the newspaper from 23 September 2020.

The Myanmar Press Council has submitted a request to the President to lift the restriction for media workers in light of its crippling impact on the industry. A member of the Myanmar Press Council, Myint Kyaw, commented: “I don’t think the government simply forgot to exempt the media. Maybe the government thought state-owned media would be sufficient to keep the public informed and that people could also get information from health authorities. The government failed to exempt the media, in my view, because it does not understand the nature of the media environment. Or it believes private media are not important” (Irrawaddy 10 Oct, 2020 ) .

In fact, in the beginning of coronavirus pandemic in Myanmar, authorities took advantage of the pandemic by persecuting independent journalists, attempting to shut down media sites and further restricting public access to information. On March 23, Myanmar’s Ministry of Home Affairs designated the Arakan Army (AA) as a terrorist group under the Unlawful Associations Act.

The next day, the government issued an order to ban access to a number of independent news websites for supposedly “spreading misinformation.” Sites targeted include Development Media Group (DMG), Narinjara, Karen News, Voice of Myanmar and a number of other independent news agencies, including some that operate in local ethnic languages.

On March 30, Nay Myo Lin, the editor in chief of Voice of Myanmar, a Mandalay-based news site, was arrested, purportedly for interviewing an AA member. He has been charged under anti-terrorism laws.

On the same evening, police raided office of Narinjara News in Sittwe, capital of Rakhine State. Three reporters were detained and the editor went in hiding. Police also searched the house of Hline Thit Zin Wai (AKA Tha Lun Zaung Htet), the editor in chief of Khit Thit Media, a Yangon-based independent news site, for republishing the Voice of Myanmar interview with an Arakan Army member.

In response of Myanmar’s harassment on the media, 250 civil society groups released their statement on 2 April, 2020 expressing concern that the government was taking advantage of the corona pandemic in order to censor legitimate information.

Meanwhile the Myanmar Press Council submitted a request to the military chief and he military-controlled Ministry of Home Affair to drop the case against the journalists and lift the restriction on press in times of coronavirus pandemic. Later Myanmar authorities dropped its accusations against the journalists and allowed to reopen the news websites. However, COVID-19 is a perfect storm for us.

Lockdowns and restrictions have created economic uncertainty. It has led to a steep decline in advertising revenues for news organizations. With distribution systems devastated, a major source of revenue has dramatically dropped, while fixed costs such as rents and staffing still have to be paid, inevitably many publications have decided to downsize and layoffs.

My organization, The Irrawaddy, is relatively small. Before COVID-19, we had 80 people including journalists, correspondents, marketing stuff, IT team, and administrative staff. Now we have dropped down to forty.

Overall, we are struggling to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic which we have never expected and experienced in our lifetimes while also trying to confront the need for various forms of internal change.

Currently The Irrawaddy is turning our newsroom into a hybrid model – with some staff in the office, some working from home, and some in the field. Since the beginning of the first wave of COVID-19 at the end of May, as the government introduced lockdowns and safety restrictions, we have changed the way we produce news.

Almost overnight, our newsroom has completely changed from physical ones to virtual ones. Unexpectedly we have experienced a dramatic change to our workflows, including online conference, remote editing, and virtual brainstorming. Our newsroom has been forced to rely heavily on Zoom and Messenger to support working from home practices. Yet, at this point, I’m concerned that it makes us less creativity at some levels.

Journalists need physical contact to debate ideas, share thoughts, and to develop contents. Of course, for people who know each other well, it’s possible to work from home efficiently. But doing so lacks the unexpected and immediate conversations that can sometimes lead to great ideas. Furthermore, the health and safety of staff reporting on the ground also is another concern.

In late October, 10 journalists including from Yangon tested positive for COVID-19 (FOJO April 2020). And 90 journalists were admitted to facility quarantine centers as they had a close contact history or secondary contact with confirmed cases. According to the 2016 report of 5th Myanmar Media Development Conference, Myanmar has about 2,000 accredited journalists across the country, but some believe the actual number could be higher than that. Due to lack of archives and updating system, the working journalist population remains unknown until now. In order to oversee this data crisis, the Press Council says it is documenting, but the end is not in sight.

Meanwhile many journalists have said that they were challenged to secure their jobs. During one event the Myanmar Press Council and UNESCO jointly launched comprehensive guidelines for journalists to report on COVID-19 based on professional standards, while protecting themselves from physical and psychological risks, Ohn Kyaing, the late Chairman of the Myanmar Press Council, said that since the COVID-19 outbreak, 80 journalists had lost their jobs in Yangon alone and more than 300 journalists across the country had reached out to the Council for support. As such, we fear that these numbers will definitely increase by the end of year 2020.

When life is hard, many unemployed journalists earn a living by selling foods in the streets, online salesmen or became deliverymen for businesses despite the high risks outside. In response to this situation, Myanmar Press Council (MPC) initiated a one-time COVID-19 relief package –cash payments – for individual journalists. It offers 2 lakhs of MMK (approximately US $160) for journalists who contracted COVID-19 and were admitted to hospital for medical treatment and to people under virus surveillance centers while those under home isolation are given 1 lakh of MMK (approximately US $80). Until the end of September, MPC distributed COVID-19 financial aid to 87 individuals (FOJO April 2020).

Another non-profit group, the Committee on Social Welfare for Journalists-CSWJ also contributed 3 lakhs of MMK (approximately 240 USD) for virus infected journalists and 1 lakh of MMK for quarantined groups. The group was able to support 53 reporters in September. The Ministry of Information also stepped in. In a virtual meeting with six non-profit local media networks in October, the ministry agreed to support 30 million MMK financial aids.

Two groups among those recipients, the Myanmar Journalist Network (MJN) and Myanmar Women Journalists Society (MWJS) handed out financial relief for the journalists in its own networks while Myanmar Journalist Association (MJA) donated to the central Covid-19 prevention department.

However, you will hear not only the bad news, but also the good. Despite COVID-19 restrictions, Myanmar authorities allowed the journalists to report freely during the election’s periods. On the election day of 8 November, we observed and reported that millions of people voted, with long lines outside polling booths, which opened at 6 am local time.

Irrawaddy journalists from the different regions of Myanmar used Facebook’s Livestream app through their mobile phones to cover the election day for live reporting. We received over 100,000 viewers for each broadcasting within an hour.

Television broadcasts also showed early ballots being counted in the presence of candidates, election officers and observers. On that day the most popular election coverage was Mizzima live broadcasting. State-owned Myanmar Radio and Television (MRTV channel), however, was heavily criticized by the independent journalists and political commentators for its lack of election day coverage. Many observers pointed out that state-owned media funded by taxpayers’ money should not be used just for propaganda, but to be reformed into public service broadcasting.

In an interview with Aung Hla Tun, the deputy minister for information and sports ministry, recognized that the role of independent news media is essential to a democracy. He said: “Overall, some media outlets have found that they are more professional and ethical than I expected. I am very pleased to think that we now have quality media that we can count on for the future of the country” (Zin Lin Htet 18 Nov, 2020).

Still Myanmar is struggling to get back to normal for not in terms of democratization, also making better public health.

Another good news is that Myanmar is planning its purchase, distribution and vaccination of COVID-19 as the United Kingdom has begun vaccinating its citizens with a fully vetted and authorized the Pfizer COVID-19 shot. Hopefully we can begin to control the pandemic in 2021. At present, the decision for purchasing a vaccine will be taken by the central committee on COVID-19 Prevention, Control and Treatment led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

In the meanwhile, we still need to follow safety measures. Practicing and implementing the health authorities’ safety guidelines, properly wearing masks, often washing hands and practicingsocial distancing are the golden rules whenever we go outside to do our reporting.

Note

- 1 The Law Amending the Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases Law https://www.mlis.gov.mm/mLs-View.do?lawordSn=7794 (Accessed 10 December, 2020)

References

- Committee on Social Welfare for Journalists. Facebook Group. https://www.facebook.com/Committee-on-Social-Welfare-for-Journalists-CSWJ-105156184531225/ Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- Fifth Conference on Media Development in Myanmar. Inclusive In dependent Media in a New Democracy. 7-8 November, 2016. https://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/Report_5th_Conference_on_Media_Development_in_Myanmar_2016.pdf Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- FOJO Media Institute. April 2020. Covid-19 Second Wave: A Fragile State for Myanmar Journalists. FOJO: Media Institute, Linnaeus University. https://fojo.se/en/covid-19-second-wave-a-fragile-state-for-myanmar-journalists/ Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- Free Expression Myanmar. 2, April 2020. 250 Organizations Condemn Myanmar Government Order to Block Websites. http://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/250-organisations-condemn-myanmar-government-order-to-block-websites/ Accessed 10, December, 2020.

- Irrawaddy. 10 October, 2020. Will COVID-19 Lockdown Restrictions on Myanmar News Media Undermine the Work of Journalists During a Time of National Crisis? https://www.irrawaddy.com/dateline/will-covid-19-lockdown-restrictions-myanmar-news-media-undermine-work-journalists-time-national-crisis.html Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- Ministry of Health and Sports. 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Surveillance Dashboard https://mohs.gov.mm/Main/content/publication/2019-ncov Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- Myanmar Press Council. 2020. http://myanmarpresscouncil.org/ Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- Myanmar Journalists Association. 2020. Facebook Group. https://www.facebook.com/mjournalistsa/

- Nyein Nyein. 4 December, 2020. Myanmar Moves Ahead with COVID-19 Vaccine Plans. Irrawaddy. https://www.irrawaddy.com/specials/myanmar-covid-19/myanmar-moves-ahead-covid-19-vaccine-plans.html Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- UNESCO. 6 July, 2020. New guidelines for Myanmar journalists to report safely and professionally on COVID-19 https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/new-guidelines-myanmar-journalists-report-safely-and-professionally-covid-19 Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- U.S. Embassy in Burma. COVID-19 Information https://mm.usembassy.gov/covid-19-information/ Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- Zin Lin Htet. 18 November, 2020. မီဒီယာမိတ်ဆွေများအားလုံး ို ျေးဇူးတင်တယ်. Thanks to all the Media Friends (Burmese) https://burma.irrawaddy.com/opinion/interview/2020/11/18/233574.html Accessed 10 December, 2020.

- Yeni (a) Myo Min Oo is a senior editor at The Irrawaddy. He joined The Iraawaddy in 2004 and his current position is Editor-in chief for Burmese language edition since my organization moved back to Myanmar’s business capital Yangon. From 2007 to 2013, He was the news editor for both English and Burmese language editions at The Irrawaddy when the office was based in Chiang Mai, Thailand. From 2004 to 2007, He was a reporter at The Irrawaddy. In 2012, He received the degree of Master of Business Administration (International Business) from Payap University at Chiang Mai, Thailand. His project submitted for the degree was “Critical Success Factor of Social Enterprises: A Case Study of Five Social Enterprises in Chiang Mai, Thailand.” His current responsibilities are mainly writing editorials, opinion page editing, strategic planning, content development and client relation.

Comment

|

DiscussantYoshihiro Nakanishi(Center for Southeast Asian Studies Kyoto University) |

If you look at the history, until 2011, the media in Myanmar was under very tight state control, with the censorship agency checking every article in both newspapers and journals. Under these circumstances, Myanmar watchers like me had to rely on information provided by media based outside the country. Of these, The Irrawaddy Magazine was one of the best sources. The magazine has had a high reputation for its quality of reporting on the politics and foreign relations of Myanmar.

With the political transition in 2011, the state substantially reduced the activity of its censorship apparatus and independent journalists have emerged inside Myanmar after fifty years of military rule. Most journalists I have met in Myanmar are in their 20s and 30s. They are young and energetic, but less experienced. They probably need some more time to develop their skills as journalists. However, the environment in which the journalists work may not give them enough time to do this, because information technology is fundamentally changing the business model of the journalism. The paper press is heavily impacted by the internet.

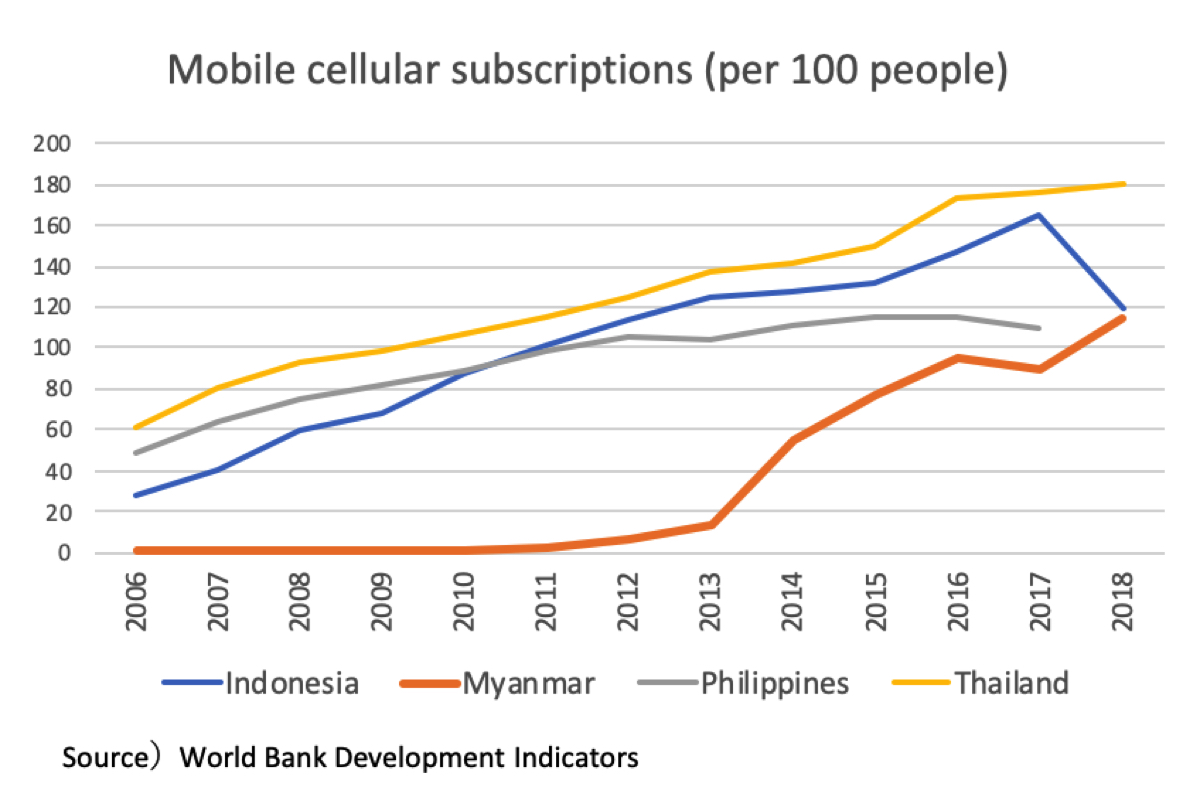

In the graph below we can see the dramatic rise in mobile cellular subscriptions in Myanmar since 2013 as well as where the country stands compared to Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia (Source: World Bank Development Indicator). The landline telephone still has low penetration rate in the country. More importantly, most of mobile phone users in Myanmar are smartphone users who skipped the pre-smartphone stages. Due to this rapid expansion of smartphone use and stage-skipping, so-called “leapfrogging”, people of Myanmar can now access large amounts of information in the cyber space with less investment, causing the print media to lose customers and bring the industry to a tipping point.

The corona crisis seems to be accelerating this leapfrogging effect in the country as more news reporting moves from print to online media around the world. Even if we overcome the current crisis soon, communication through the internet will continue to be essential for Myanmar, as a post-corona world will rely more on online communication than the pre-corona world. This means the people in the world will also be increasingly forced to face the downsides of the technology as well, such as the rapid spread of disinformation, fake news, and hate speech.

At least so far, the Myanmar government has not taken sufficient measures against such downsides, and it sometimes curbs freedom of expression, especially freedom of the press. For example, it arbitrarily uses various laws and regulations to interrupt the activities of journalists. As Ko Ye Ni mentioned, under the current crisis, the Disaster Management Law has been added to the government’s cache of legal weapons that it can use against journalists.

Ko Ye Ni himself was sued last year by Myanmar’s military under Article 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law, with the accusation that the Irrawaddy’s reporting on the conflict in Rakhine State was not neutral. The military later dropped the lawsuit, but this kind of SLAPP lawsuit1 is likely to have a chilling effect on all news media in Myanmar, making journalists feel uneasy and hesitate when they report on the military. Indeed, one journalist friend of mine told me that he is very careful when he publishes articles critical of three forces, namely, the military, the Buddhist monks, and Aung San Suu Kyi. Even though there is no official censorship as there used to be, such arbitrary prosecution threatens press freedom. The current corona crisis brings more tension to the relationship between journalism and the government in Myanmar.

Note

- 1 SLAPP, a strategic lawsuit against public participation.

Nakanishi Yoshihiro is an Associate Professor at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University. His research focuses on the politics and international relations of Myanmar, Southeast Asia, and Japan. Nakanishi previously worked with the Institute of Developing Economies (IDE-JETRO) and was a visiting scholar of the Southeast Asia Studies Program at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), a division of Johns Hopkins University based in Washington D.C. He is the author of Strong Soldiers, Failed Revolution: The State and Military in Burma, 1962-1988 (National University of Singapore Press & Kyoto University Press, 2013)

Other Presentations

- Slow Virus Response, Quick Rights Suppression: The Philippine Covid-19 Experience

- Reporting on Covid-19 amidst Political Upheaval in Malaysia

- Regressive Indonesian Freedom? The Rise of Digital Harassment against Journalists and Civil Society in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic

- Thai Press’ Over-reliance on Government Information about COVID-19